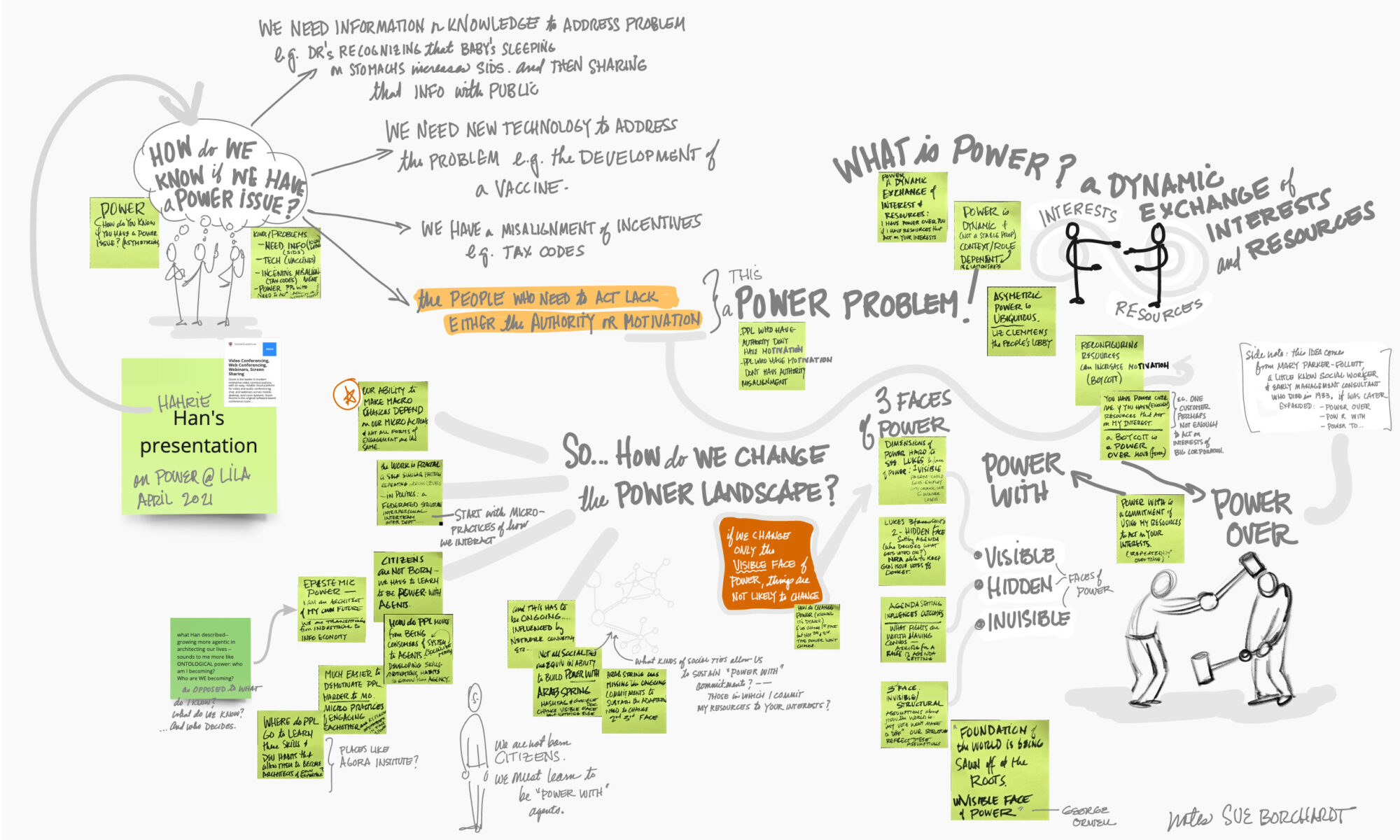

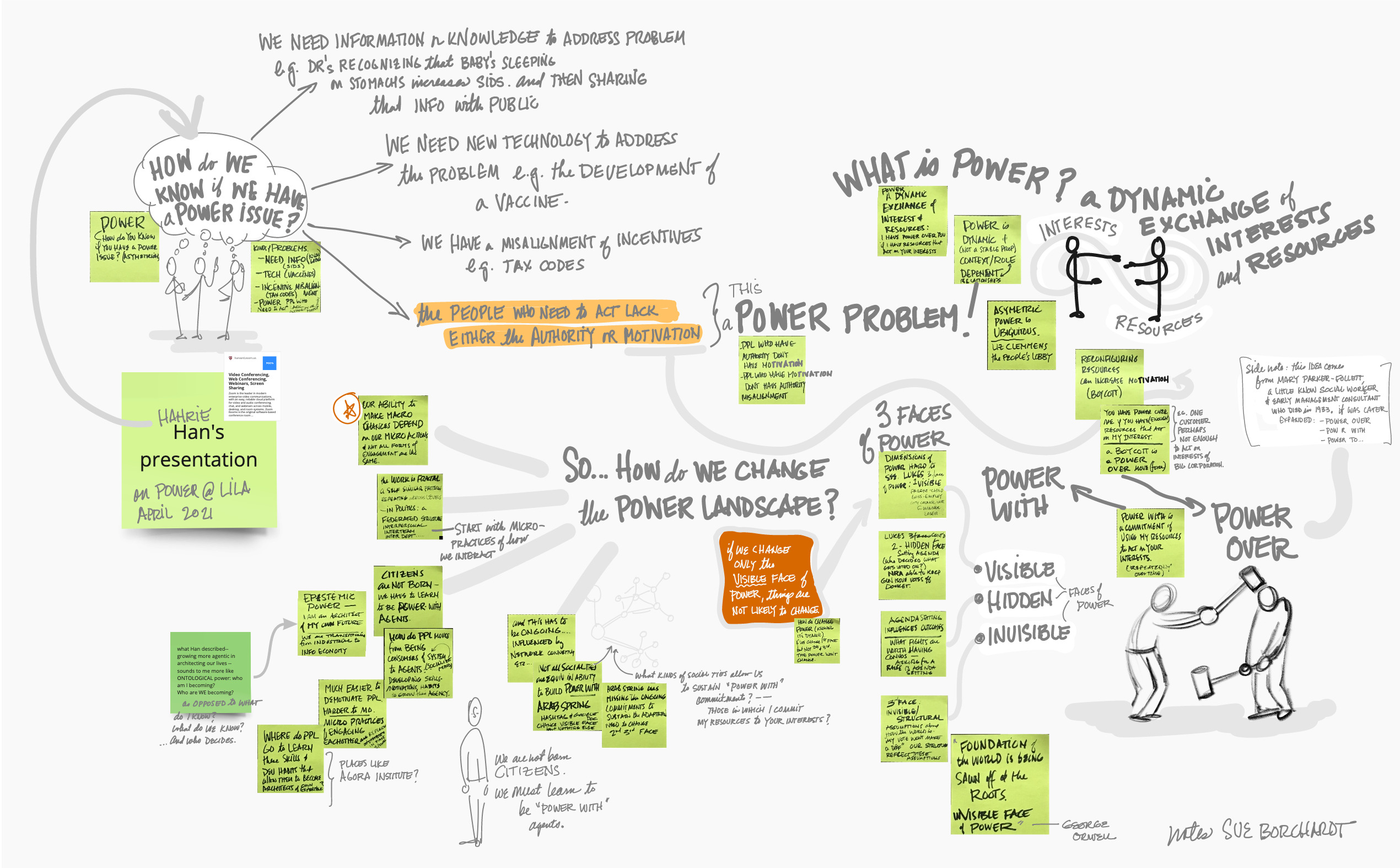

I’ve been thinking about Hahrie Han’s Learning Innovations Lab (LILA) talk for the April 2021 gathering (the first of two). Han opened her talk by asking “How do we know what kind of problem we have?” I took some notes (in the image), and the rest of this post outlines things that stood out for me, as well as some puzzles on connecting her ideas to the cynefin sense-making framework, and my attempt to try our her lens on #power in a specific context, i.e. prison reform.

How do we know what kind of problem we’re facing?

- Do we have an information problem? (e.g. a new understanding of sudden infant death syndrome.) Note: French and Raven might say this is the “Expert” seat of power

- Do we have a technical problem? (e.g. we need a new vaccine)

- Do we have an incentive problem? (e.g. a tax-code that rewards a behavior that makes the problem worse). Note: French and Raven’s reward power.

- Do we have a power problem? Han defines this as: the people who need to take action to the address it either don’t have the authority or the motivation to address it. (SB question: what about the access to resources or the knowledge?)

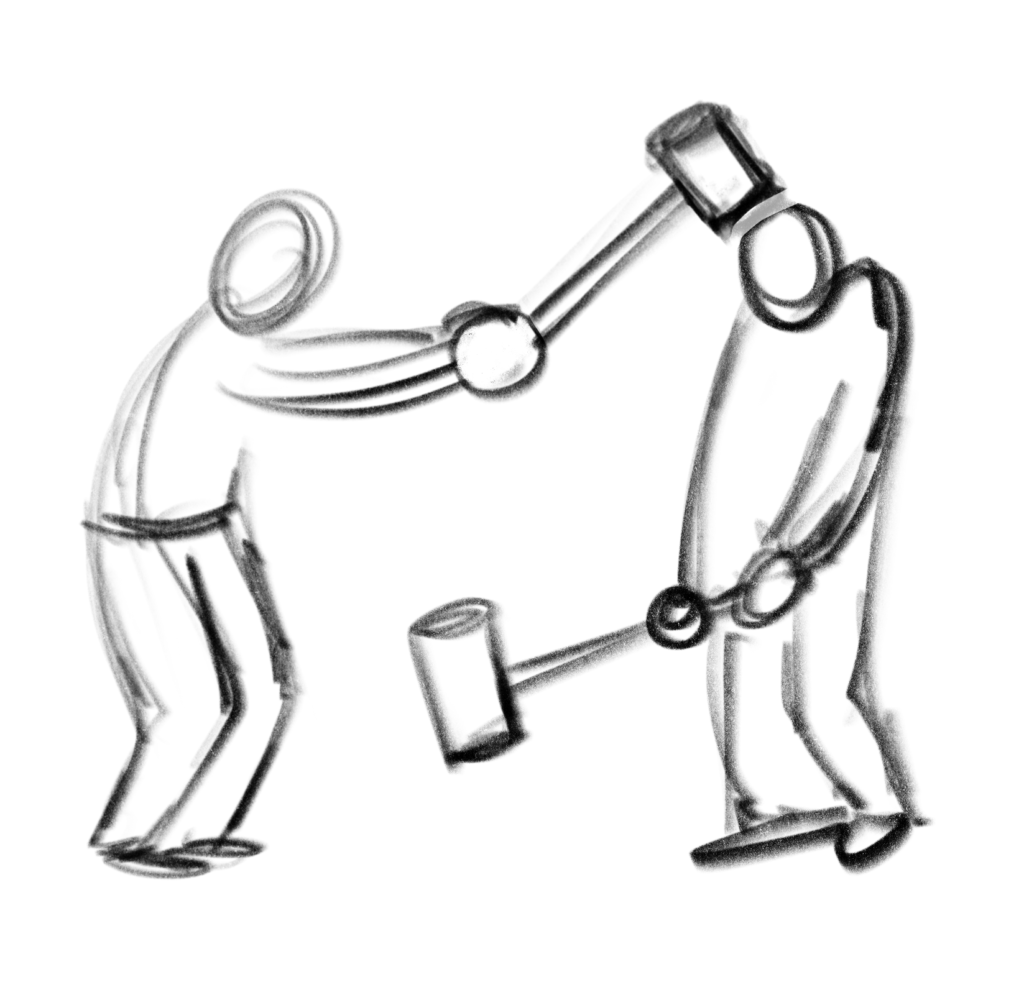

Han frames power as: I have power over you if I have resources that act on your interests. She says I have power with you if I commit my resources to your interests. (Note: power over and power with are ideas first introduced in the early 1924 (!!) by social worker and early organizational management thinker Mary Parker Follett in her book Creative Experience)

Han’s buckets of problems are useful, but it also seems to me that all this is highly entangled. For instance access to information is one of the aspects of power, no?

Han illuminates the “suitcase word” power by bringing in Steven Luke’s three faces of power: visible, hidden, invisible. (is this similar to known, knowable, unknowable to borrow some language from Snowden?)

- the visible face of power is that of leaders. These are the clear leaders, usually with a title, i.e. politicians, CEOs, etc. (Note: French and Raven call this the legitimate seat of power)

- the hidden face of power: who sets the agenda? Who is blocking what gets talked about or voted on. i.e. the NRA is a hidden face of power that has succeeded in keeping gun laws from reaching congressional vote. (Hmmm – is this referent power in French and Raven’s model?)

- the invisible face of power: assumptions and beliefs about the world that become mirrored and embedded in the collective structures (institutions, cultures, policies, laws). So basically assumptions and beliefs feed forward into structure. She shared a couple examples but I’m not sure I captured them well: My vote doesn’t matter so I won’t vote, only 50% of people will ever vote so we need to structure the process to account for that .

It seems to me that there is an element of knowing/information that underlies the invisible face of power. I’m thinking this could be tacit or unconscious, but it could also be idealistic, dogmatic (e.g. an espoused belief that people need to be protected from themselves). To take this a bit further, the hidden face of power that the NRA exerts seem to be fueled by an invisible face of power — beliefs about how safe or dangerous the world is, and how we think about “other” people in general. Do 2nd amendment rights folks believe humans are inherently selfish and competitive, and so dangerous?

I’d like to put a pin in that question and shift to looking at an actual challenge: a non-profit that seeks to change the practices in correctional institutions to be more humane, specifically to end the use of solitary confinement. In this problem landscape…

there are a wide range of interests, those of…

- people who are incarcerated

- their families

- victims

- correctional officers

- wardens

- politicians

- people working for peace like me and my fellow board & community members at Interfaith Action for Human Rights, Quakers, etc… as well as orgs working on corrections reform, e.g. Vera institute of Justice, Quakers, and many others.

and the resources acting on those interests (to go with Han’s frame of power) are layered…

- taxpayer dollars, (in a municipality, state, or country)

- profit, e.g email and phone providers, industries using prison labor (business and industry)

- prison commissary and the cash to buy from it (at the individual level, both behind the walls and outside as families provide resources to their members who are incarcerated )

- the informal interpersonal priosn economy: a pack of cigarettes that I have and the negotiation that takes place around my interests and your interests that influence what I can exchange them for.

A wonder: how do the clear, complicated, complex, chaotic, and aporetic domains of cynefin map onto Hahrie Han’s “problem categories” of information, technology, reward, and power? Can these frameworks (Han’s and Snowden’s cynefin) inform one another and, in turn, inform the strategy an organization like IAHR could craft to actually bring about an end to the use of solitary confinement?

And now that I’ve brought strategy into the conversation, I am wondering what would happen if I mapped some of these power relationship, stakeholder interests, and resources on a Wardley Map. It feel quite daunting to really unpacked the relationships: the interests and resources of those involved.

The problem of ending solitary confinement intuitively feels like a complex one (in the cynefin sense), but could it really just a matter of power? If it was, someone who had the power (e.g. the State secretary of corrections here in MD for instance) could end the practice. .. but I don’t think that’s really true. If we look at this from the larger lens of human rights, humane treatment, and human dignity, that can only come about inside a prison if the thinking and assumptions (and subsequently the actions) of the guards is shifted in a way that they believe and treat incarcerated people as worthy of that treatment. Is it Lukes’ [[invisible face of power]] what plays out as behavior here?

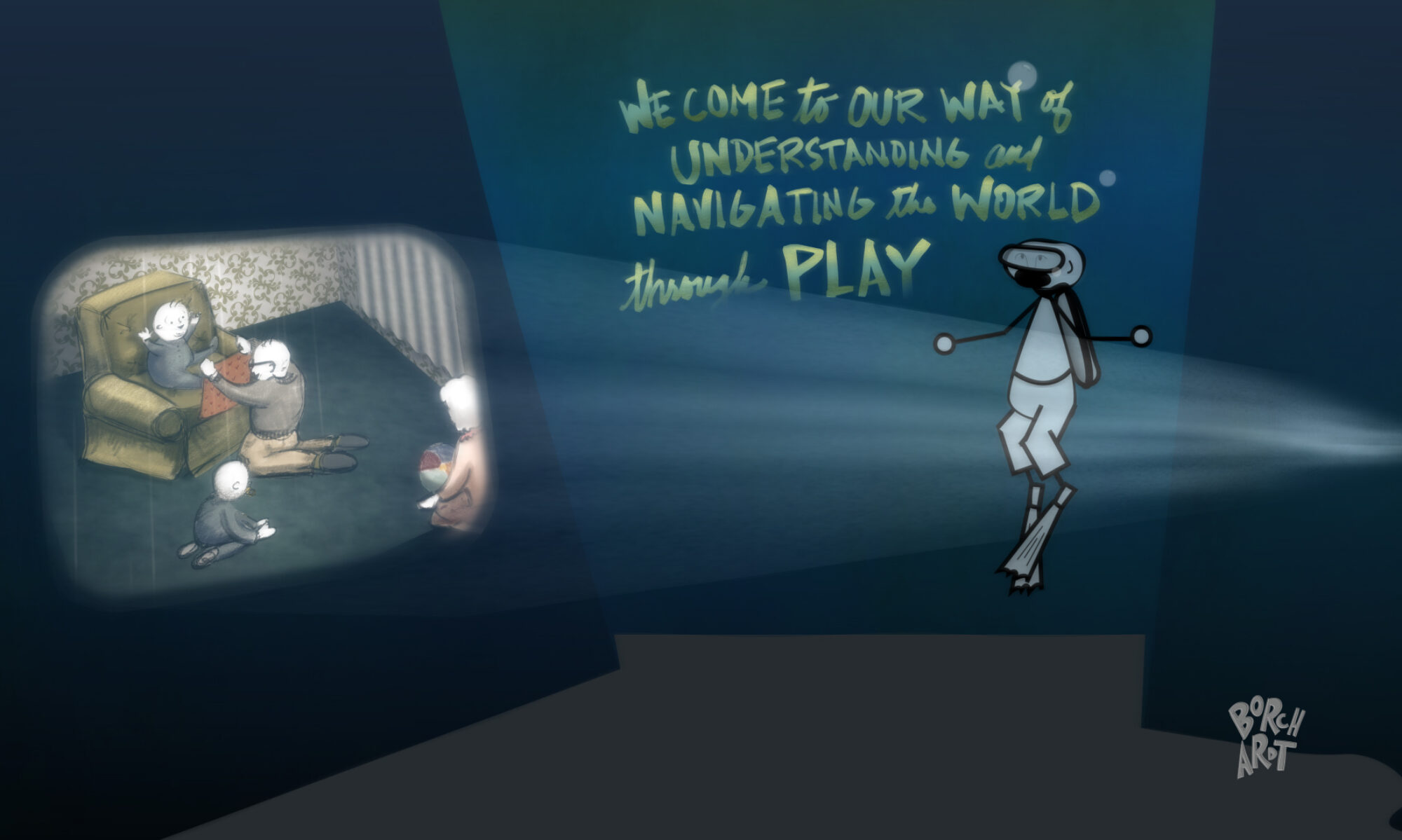

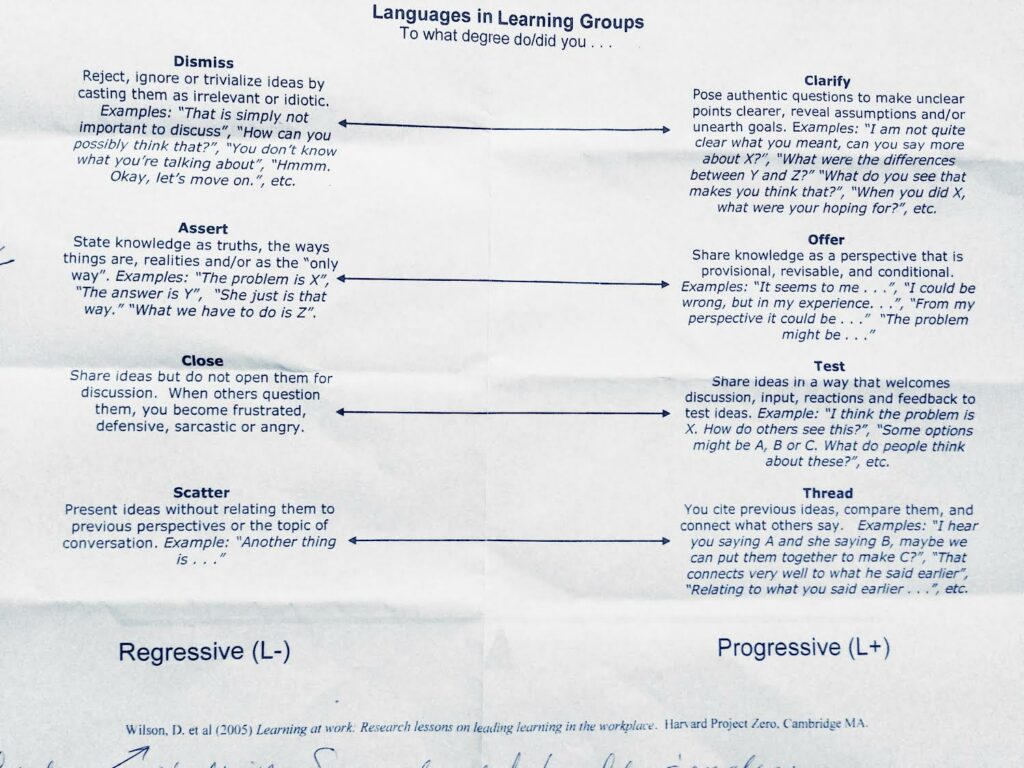

BIG question for me: Han suggests that individual agents CAN do things to influence these big problems rife with asymmetrical power. Is this true? Which agents? Correctional officers? people who are incarcerated? One of the critical points Hahrie Han makes is that skills of power with (those where I commit my resources to act on your interests) must be learned. In her talk, she makes this point in the context of citizenship (an inherently power with orientation), noting that citizens are not born. Citizenship must be learned. So how do we cultivate power with orientations, beliefs, and micro-behaviors inside a prison? When I think of micro-behaviors I immediately think of Daniel Wilson’s language of learning conversational moves (see image). Indeed these moves not only support the learning of groups but they are indeed skills that most individuals would need to develop and practice. As it happened, the most powerful lessons I received in becoming more “progressive” in my own conversational (sense-making) “moves” was in the ways they were modeled in Daneile Wilson’s classroom (I was his teaching fellow in a course on group learning) as well as in the norms that are enacted at LILA (where I was a member of the facilitation team and where Hahrie Han offered this content).

On a tangential line of thought, Han’s power definition is an interesting one, even as an individual invitation to reflect on my own agency. She says I have power with you if I commit my resources to your interests. Well of course, each of us uses our resources to act on our interests but invites some interesting questions:

- how am I using (leveraging) my resources to act on my interests?

- how we do I understand my own interests (needs, motivations, desires, agendas). For instance, I might espouse a commitment to be an anti-racist but my need for psychological safety might be an invisible face of power impeding my actions towards becoming an anti-racist.

- What do I consider my most valuable resources? My labor, my attention, my cash, my cash reserves? This last one does seem to buy me a lot of power/freedom from other people acting on my interests, at least in freeing me up from contractor/client relationships (or boss/employee relationships) in working as a research artist